Many of you are probably wondering “What is all this I hear about a new Glasair Super Ill?” Well, prior to Sun n’ Fun this year, our Glasair III demonstrator, N54OLP, went though a complete metamorphosis to become N401KT.

Yes, we did fly it to Flight level 330, and we and achieve speeds in excess of 350 mph. Yes, it was still maintaining an honest 2,000 fpm rate of climb at 32,000 feet. Yes, I was trying to set a new non-stop speed record from Arlington to Lakeland with a total of 167 gallons of fuel on board.

Yes, we did fly it to Flight level 330, and we and achieve speeds in excess of 350 mph. Yes, it was still maintaining an honest 2,000 fpm rate of climb at 32,000 feet. Yes, I was trying to set a new non-stop speed record from Arlington to Lakeland with a total of 167 gallons of fuel on board.

Why were we doing this? The idea was to see what the potential would be for some new speed modifications to the Glasair line. We learned quite a bit from this initial research and development, but we have more questions to answer yet. As research progresses we will certainly keep you posted on any new options that might spin off from this work.

We began the project by using a laser interferometer to produce a very accurate loft of N540LP. This data was fed into a sophisticated three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis to see what would happen to the Glasair at very high speeds in the Mach .6 to .7 range at 37,000 feet. We found out some very interesting things.

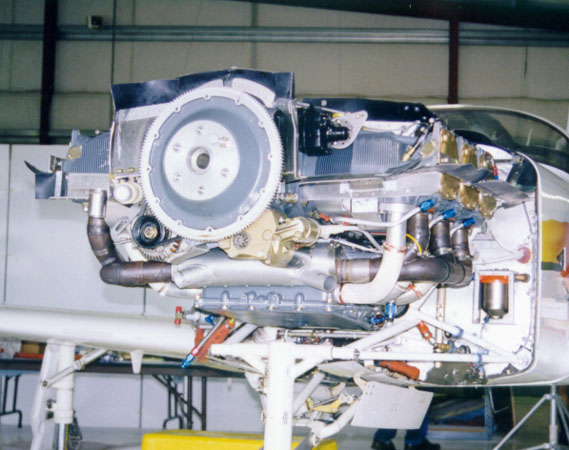

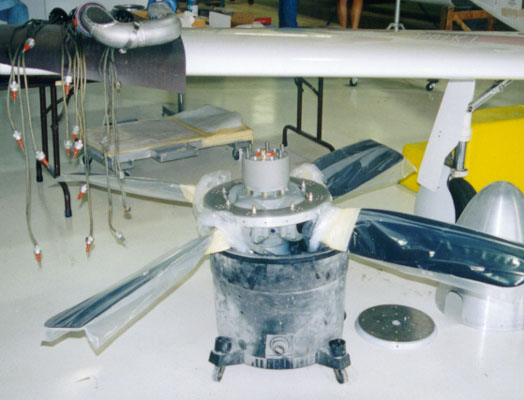

Back in the shop, N540LP was essentially gutted down to the basic airframe. We installed a Lycoming IO-540-AA1B5 engine with low-compression pistons and all the necessary accessories for high-altitude performance. To this was married a state-of-the-art turbo intercooler installation and a totally new, wide-chord four-blade Hartzell propeller (125 pounds worth). A highly modified cowling was designed and built to house the new powerplant installation. The look of the finished product was nothing short of brutish.

Back in the shop, N540LP was essentially gutted down to the basic airframe. We installed a Lycoming IO-540-AA1B5 engine with low-compression pistons and all the necessary accessories for high-altitude performance. To this was married a state-of-the-art turbo intercooler installation and a totally new, wide-chord four-blade Hartzell propeller (125 pounds worth). A highly modified cowling was designed and built to house the new powerplant installation. The look of the finished product was nothing short of brutish.

The instrument panel was also totally new, and we had to have a custom Data Processing Unit made by Lance Turk of Vision Micro Systems for the new fuel flow rates and the turbine inlet temperature (TIT) function.

I had to wear a helmet and used a diluter demand oxygen system with pressure mask. This was a new experience for me. At 33,000 feet, it’s cold, and you have to concentrate on clear word pronunciation. The oxygen mask kind of tickles your face when you talk because the system is trying push oxygen into your lungs.

To date, we haven’t had the opportunity to even begin to explore the full flight envelope of the aircraft, to fully realize what the highest speed and altitude will be. The “numbers” say that we should easily be able to cruise at 350-360 mph and to reach 400 mph with a little more tweaking.

We did this all using only the short wingtips and slotted flaps, with the only aerodynamic change to the airframe being the installation of a larger rudder. This development program, like many, wasn’t without its difficulties. Honestly, I think we were pushing just a little too hard.

Lesson Learned #1: Do not be in a hurry!

The plane first flew on the afternoon of April 14. It flew well, just like any other Glasair III. Throughout the week, we proceeded to expand the flight envelope, putting in a little more than the ten FAA-required hours on the engine installation before attempting the record flight. The weather was beautiful the entire week of flight test, which was very helpful.

On Saturday, April 18, I began the record flight from Boeing Field in Seattle to wherever the tailwinds would take me. (I had to go to Boeing to get the oxygen bottle filled.) I remember the ramp guy at Galvin Flying Service saying, “You look like you’re doing the Charles Lindbergh thing.” I responded, “Well, kind of!”

I departed from Boeing Field climbing for Flight Level 290 loaded with oxygen, cold-weather gear, every approach plate and chart imaginable, and 167 gallons of fuel. My gross weight was 3,200 pounds. My climbout, even with the extra weight, was still respectable at 1,000-1,400 fpm.

I had filed direct to Wichita, and I was climbing out on course when the radios began becoming quite scratchy. Upon reaching 7,000 feet, it was becoming increasingly difficult to communicate with ATC. At 9,000 feet, I could barely understand the controller.

After all the sweat and blood to get to this point, I reluctantly made the decision to cancel IFR and go VFR back to our home airport, Arlington Municipal. This was a very difficult decision, for we had all worked so hard to get this point. Most of the company crew was either already at Sun n’ Fun or on the way by airliner, and I so badly wanted to join them there in the Super III.

But, I couldn’t carry on an IFR flight without radios, especially one of this nature. After several radio transmissions back and forth between ATC and myself, I was able to get ATC to understand that I wanted to cancel IFR and get VFR vectors back to Arlington.

I was about five miles southeast of Arlington at 5,000 feet when I noticed the tachometer was reading only about 2,450 rpm. At full power, the engine should have been turning about 2,550 rpm At this point, I immediately started scanning everything engine4elated: the oil temp was 212°F, and the oil pressure was down to around 60 psi. This was not good.

Of course, my first thought was, “This can’t be happening.” I throttled back, hoping to “baby” the engine, and headed directly to Arlington. When I was about half a mile southeast of the runway at 2,500 feet, the oil pressure went to 20 psi. At this point I really throttled back.

Well, about fifteen seconds later the engine “blew up” in front of me. Oil covered the windshield, and I had little time to plan my descent and landing location. Here I was at my home airport, on downwind and perfectly set up for landing. The only problem was I was 800 pounds over gross!

I instinctively feathered the prop, leaned the mixture, turned the fuel and mags off, and then everything electrical. All the while flying the plane, trying to decide where to put this baby down. Traffic was landing on Runway 16, and I came in on the left downwind on the east side of the airport. (Editor’s note: Ordinarily, the left-hand pattern for 16 at Arlington is only for gliders, but by the time Bob got there, he was qualified!)

I knew I had the field made, but there was traffic everywhere. I began to lower the landing gear, which goes against my own personal rule of never lowering the gear unless you know you can land on a hard runway. I quickly realized this would not work, as my sink rate increased dramatically. With the extra drag of the gear and the added weight of the fuel, N4O1KT felt like a flying brick. I immediately put the gear back up. With no alternator to assist the battery it seemed to take an eternity before the gear finally came back up into the wells.

I opted to land gear-up in the grass on the westside of the runway. This decision, I believe, saved me and the airframe.

I came in “over the fence” at about 130-140 knots and touched down at who knows what airspeed. The touchdown was loud but smooth… until I encountered the taxiways. The first one launched me back into the air about thirty feet. It definitely hurt, because afterward the G-meter read +9—off the scale. Ouch!

All the while I was thinking to myself, I do not want to flip this plane. Everything was fine after I landed the second time… until I hit the next taxiway. Again, I was launched into the air, only about twenty feet this time. The right flap departed the scene at this point. After I landed again, I finally came to a stop off the southwest corner of the runway in between the runway and the road.

Lesson Learned #2: Never quit flying the airplane!

The rudder worked quite well, even in the grass. From the time I lost the engine to the time I touched down was not very long-maybe a minute or less. You really don’t have a lot of time to make the right decisions. But if I had not continued to eke every last bit of control out the airplane as it decelerated, I could easily have flipped over, and the outcome of this story might have been much different.

May I emphasize one point? The Glasair is one tough airplane! I wouldn’t have wanted to be in any other airplane under these circumstances. The four-bladed prop and the flaps, which were down 200, took all of the impact loads. The running joke in the shop is that we are going to make the flap tracks out 3/8″ thick steel next time so there won’t be any damage at all!

Initially, after I had come to a stop, I smelled around for fuel leaks and turned off the oxygen. My first thought was, “This didn’t really happen, did it?” Yes, it did. I hopped out of the plane, and my second thought was, “I just broke our company plane after all the work our mechanics had put into it.”

After I came to a stop, people were bailing out of restaurants, hangars and buildings wondering if I was all right. It was 2:12 in the afternoon. I was all right, and I was not even scratched. I could have been seriously injured or worse and could have totally destroyed the plane. My route of flight, if I had not had the radio problems, would have placed me directly over the Cascades without an engine in a flying bomb. I did have a parachute, but who knows if I would have been able to bail out?

The radios seem to be okay now, but there are some issues with the old carbon microphone in the oxygen mask that may have been part of the problem.

I am very thankful to be alive for many reasons. I was calm when the engine blew a rod on the forward left cylinder, creating a gaping, 6″ diameter hole in the crankcase. People asked me afterward, “Weren’t you nervous?” No, I wasn’t. I do not know why, but I did have a job to do and every decision had to be done just right. I did not have time to panic.

This next part of story is a testament to the accuracy of the news media. Don’t believe everything you hear or read in the news. We all know this is true, but once you’ve experienced it firsthand, it’s a bit shocking. Local news camera crews were at the scene of the incident, and not even once did they try to talk to me to find out what actually happened. They did, however, interview someone who witnessed the incident who really didn’t know what he was talking about. I was okay, what news was that? I guess I wasn’t bleeding, so why bother. The story apparently wasn’t sensational enough, so they had to invent something

Of course, my mother was among those who saw the telecast that said I was in the hospital. Even the police and ambulance people were surprised I was OK. They questioned me and had me sign a waiver that stated I was OK so they couldn’t get taken to court later if I did complain of something. The police and ambulance personnel were, however, very helpful, and I was thankful that they were on the scene if something more serious had happened.

Surprisingly, the airplane wasn’t damaged that much. The big four-bladed prop took most of the impact. After all the hoopla was over, we had a hoist truck lift the plane off the ground to see if we could lower the landing gear. Sure enough, the gear came down just fine. Some onlookers clapped when the gear came down and locked.

Ted Setzer and his dad ,Ted Sr., were very helpful that day, for which I am very thankful. Bryan Poole, our former production manager, was also at the scene with a trailer, just in case, and I appreciated his support.

With the gear down and locked, Ted towed me back to Stoddard-Hamilton in our wounded Glasair Super III. Before the news of my forced landing even hit the airwaves, I was on a jet out of SeaTac, headed to Lakeland for Sun n’ Fun. It was a long day.

We hope to get N401KT to Oshkosh this year. Marshall Whipp already has the flaps repaired and is hard at work on gear doors and other cosmetics, while Cal Spangler is lining up the various pieces of the powerplant puzzle. More on this later.