IFR Training in the Glasair Super II

Written by Craig O’Neal

It was about halfway down the Columbia River Gorge that I decided to get my instrument rating as soon as possible.

I was solo in N902S, S-H’s trusty Super II RG demonstrator, en route to the Copperstate Fly-In in Phoenix at about 1,000 feet AGL, and I was getting the living tar beaten out of me. As my head slammed into the canopy for the third or fourth time in as many minutes, I looked at the ground speed readout of 230 knots on the GPS and thought, “Well, at least it’ll be over soon.” How wrong I was.

Initial Approach Fix

The trip had begun typically enough for an autumn flight out of Arlington, which is to say with lousy weather and high spirits. The lousy weather consisted of 2,000 foot ceilings, scattered showers and the inevitable “VFR not recommended” from the Seattle Flight Service briefer (who must get tired of saying that!). The high spirits came from simply being at the controls of a Glasair (which is never a bad thing) and from having studied under some of the world’s leading Grand Masters of Sensible Scud Running (who should remain nameless, but whose initials are Tim Johnson and Ted Setzer).

However, as I dodged and weaved my way southward into a howling 60 knot headwind, the lousy weather began to get lousier and the high spirits not quite so high. The turbulence was absolutely punishing, and with the ceilings occasionally dipping below 1,000 feet, there was certainly no chance of climbing above it for a VFR grunt like me.

By the time I turned the comer at Portland into the giant Venturi of the Gorge, I had spent an hour-and-a-half covering a route that would ordinarily have taken about forty-five minutes.

And although I was pleased at my rapidly improving ability to catch my hand-held GPS in the air before it hit the ceiling, that was small compensation for my aching shoulders and disoriented innards.

Pulling the power back to around 15 inches took the sharpest corners off the bumps, but with the Gorge walls still whistling past at close to 200 knots, I felt like I was being fired out of a cannon. I thought that filing a pilot report on the turbulence would be the neighborly thing to do for any poor sap who might blunder aloft in my wake, but I couldn’t dial in the frequency to save my life. Why does King insist on such slippery little knobs?! That’s when I realized there had to be a better way.

Well, as those of you who read Bob Gavinsky’s column in last quarter’s newsletter know, an IFR rating wasn’t much help on that particular day. The moderate-to-severe turbulence I was experiencing down in the muck extended south almost to Las Vegas and vertically well up into the Flight Levels.

Nevertheless, I had decided that getting an IFR ticket would be my fall project, and even after a flawlessly gorgeous VFR flight home from Copperstate, I was anxious to get started.

Procedure Turn Outbound

The immediate questions were what to fly and with whom. The “what” was not as obvious as you might imagine. While it’s true that we pilots lucky enough to work for S-H do get a fair bit of Glasair and GlaStar time in the course of our duties, we don’t enjoy either free or unlimited access to the airplanes for personal use. This is naturally as it should be, since the airplanes are far and away our most valuable corporate assets.

It was thus with considerable trepidation that I asked Bob if he might consider letting me use one of the demonstrators for my instrument training. You can imagine my sigh of relief when he said yes!

After all, as those of you whose Glasairs and GlaStars are flying can attest, these airplanes absolutely wreck you for getting the slightest enjoyment out of flying any Wichita spam can ever again.

The idea of ponying up fifty bucks an hour for some clapped-out old Cherokee or 172 really would have tested my commitment to getting the rating.

The question then became whether to use the GlaStar or the Super II. A lot of people around the shop were surprised when I finally decided on the II. After all, the GlaStar practically flies itself, and according to the conventional wisdom, what the IFR trainee wants is precisely such a slow, stable platform— an airplane that gives the neophyte plenty of time to think while making all the hideous mistakes he or she is sure to make and plenty of time to recover from them afterwards.

The Glasair, however, is a bird of a different feather. How did one of you builders describe it in a recent First Flights column? “Skittish as a wild goat,” I think it was! Well, that’s not exactly how we’d put it in our advertising copy, but the handling is definitely… spirited!

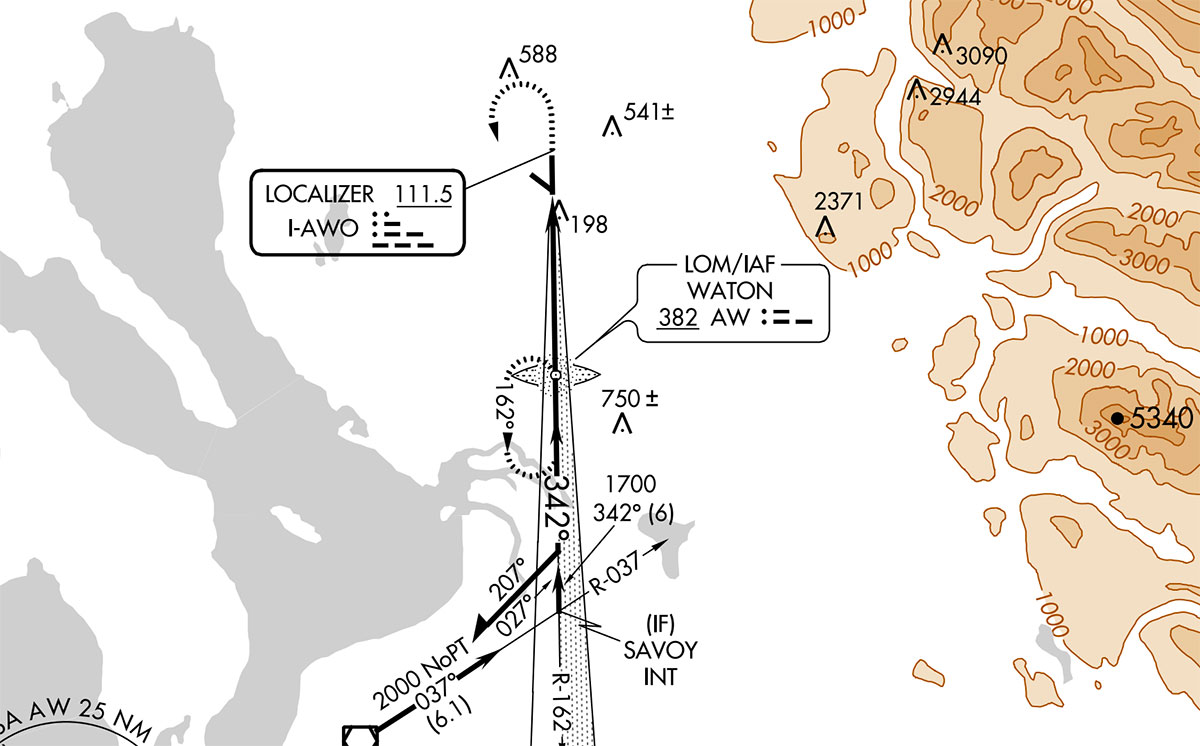

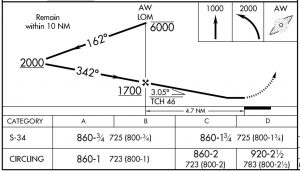

So why train for the instrument ticket in an airplane that’ll go knife edge on you in the time it takes to fold a chart and that’ll zoom through a localizer faster than Approach can say, “Call the tower when you’re on the ground; we need to talk about that one?” Well, aside from my generally contrary nature, there were a couple reasons. First, as I perused my logbook, I was startled to realize that almost half my total time has been in old Zero Two Sierra. Why not train in the airplane one is most comfortable in?

Second, to the extent that the main challenge of instrument flying lies in the approaches, why not cruise through the inevitable en route portion of the training at 180 knots rather than 130 knots? The choice of the II seemed to make emotional and economic sense.

So where to find an instructor? When Harry DeLong came to work at S-H, we were all excited about the letters “CFII” after his name and all the cheap instruction we were going to enjoy. But when I approached Harry with my plan, he mumbled something about lack of currency and ambled off toward his newly purchased Pitts S-1T with his parachute and helmet under his arm.

After repeated failed attempts to induce Harry to fly into the clouds with me, I began to conclude that maybe a straphanger like him wasn’t really the mild-mannered instrument instructor I was looking for. I mean, does “ILS” really stand for “Immelmans, loops and spins” like Harry says it does?!

Thus I found myself at the office of a small flying club at Paine Field in Everett asking the resident CFII if I could receive instruction in my own aircraft. “Yeah, that may be possible,” he said guardedly, “if it’s adequate.

What kind of airplane do you have?”

“A Glasair,” I replied.

“That’ll be no problem whatsoever!” he said, trying hard to sound casual.

“When do we start?!”

Procedure Turn Inbound

And so it began. In the early stages of the training, I think the instructor learned more than I did. “What power setting do you typically use for descents,” he asked innocently.

“Well, in smooth air, I just generally leave it at cruise and push the nose over like this,” I replied, giving the stick an authoritative nudge. Despite the goggles I was wearing, I could sense his eyes getting big as the airspeed needle eased past 200 knots, probably for the first time in his flying career.

“Yeah, that seems to work,” he acknowledged.

Later, as he took the stick for some unusual attitude recovery work, the airplane really did feel like a skittish wild goat. “Slippery little thing, isn’t it,” he said in the most nonchalant voice he could muster. After what felt to me, with my eyes clamped tightly shut, like an incredibly spastic maneuver entry, I expected to find the airplane halfway through a lomcevak, but instead I opened my eyes to a gentle climbing turn to the right, which I managed to coral with a little fingertip pressure on the stick.

“Small, smooth stick movements seem to work best,” I observed as gently as I could.

The instructor got better, though, and I certainly got my comeuppance as we moved from basic attitude flying into approaches. Flying my first ILS in actual conditions, I felt like a circus clown riding a unicycle down a tightrope while juggling plates and carrying on a technical conversation in Hungarian.

This feeling of being so far behind the airplane that it was gaining on me from behind abated pretty rapidly, however, as I learned the cardinal rule of instrument flying in the Glasair (which might also be termed the “Chicago Voting Rule”): slow down early and slow down often! This is, of course, the same cardinal rule that one must master in transitioning from lower-performance airplanes into the Glasair in the first place. Just because the airplane can go like stink doesn’t mean it always has to, and properly reigned in, the thing handles just like one of those $50-anhour Cherokees.

As the training progressed, I felt better and better about my choice of airplane. I settled on 120 knots with gear down and half flaps as the best configuration for approaches, holds and any other maneuvers that required the front part of my brain, and as long as I remembered to get stabilized that way before it was too late, things went quite well.

If I had any lingering doubts about the wisdom of training in the II, they were completely eradicated one Saturday when 902S was down for maintenance and I rented the flying club’s Grumman AA-5 in order to keep the training schedule on track. With all apologies to any Grumman enthusiasts in the readership, what a dog! I felt like I was driving a garbage truck through molasses, albeit (paradoxically) a garbage truck that was tossed around like a cork on the ocean by every little zephyr of wind. I found everything from holding headings and altitudes to making standard-rate turns to be colossally difficult in the Grumman. This wasn’t flying as I had grown accustomed to it.

Later, I loaded a safety pilot aboard Harry’s GlaStar and shot a couple approaches in it just to see what that was like. Way better than the Grumman, that’s for sure! But surprisingly, I found it more difficult to fly the GlaStar precisely than the Super II. Or perhaps more accurately, I should say that it was no more challenging to fly precisely, but you had to meet the challenge longer.

Flying an approach at 90 knots simply provided more time for my attention to wander.

Final Approach Fix

In any case, the requisite 40 hours of instrument time passed much more quickly than I expected, and I was surprised toward the end of December to find myself scheduling a checkride. It would be a memorable Christmas, one way or the other!

The examiner was based in Bellingham, about 50 miles north of Arlington, and as I flew northward on the fateful day, I was much less concerned about the flight test than about the oral. But I tell you what: punch destination direct into the GPS, rum on the autopilot and you’d be amazed how effectively you can study that little red oral test guide when the chips are down!

As it turned out, the factor that most nearly caused me to fail the checkride was nothing to do with my knowledge or skills—it was the examiner’s size!

As he unfolded his 6′ 4″ frame from the FBO’s cracked Naugahyde couch and eyed the Glasair suspiciously through the window, he said, “Nice to meet you.

Will I fit?”

Using my best airshow voice, I replied, “Oh, absolutely! We’ve had bigger’n you in there! Er… can I ask how much you… urn … weigh?”

Well, the weight and balance came out OK, he did fit (with the headset band kind of scrunched down around his forehead), and I think he even enjoyed himself. As he took the stick to put the airplane into an unusual attitude, he chuckled and exclaimed with pleasure, “Slippery little thing, isn’t it?!”

Later, on climbout after one of our missed approaches, the tower called us out to another airplane in the pattern.

“Cessna Four Five Alpha, your traffic is a Glasair on the crosswind… oh never mind, you’ll never catch him!”

“Only in my dreams,” the poor Cessna pilot replied dejectedly.

I felt like keying the mike and saying, “Listen, buddy, you wouldn’t be so jealous if you ‘d just flown a sloppy NDB approach in a 20 knot crosswind on your checkride!” but I decided that wouldn’t be politic.

Well, as you have doubtless guessed, I wouldn’t be writing this story if I hadn’t passed, and the flight home with the newly-minted temporary certificate in my pocket was an exuberant, unfettered, rolling and looping VFR extravaganza from which the gyros are still recovering!

Decision Height

What do I conclude from this experience? First of all, if you’ve ever had the slightest thought that you might someday like to earn your instrument rating, do it! And if you’ve never entertained such a thought, think it and then do it! Regardless of whether I ever see the inside of another cloud or not, the training has made me a much more precise and proficient pilot.

(Everything’s relative, after all!) The whole ordeal was also immensely

personally satisfying. This was easily the hardest thing I’d undertaken since flunking diff. eq. back in college, and the feeling of accomplishment at seeing it through is, I imagine, exceeded only by that of finishing your own airplane!

(Mine still needs a lot of work.) Second, although the myth that the Glasair is a hot ship continues to serve the myth that we’re all a bunch of hot sticks, I think we’d probably be better off overall if both the aircraft and our own abilities were evaluated a little more realistically. These myths put Glasair pilots on the horns of a paradoxical dilemma. On the one hand, insurance companies, other pilots, and sometimes even we Glasair pilots ourselves are unjustifiably afraid of the airplane, which is, when all is said and done, not a wild goat, but a very honest, straightforward craft that responds conventionally and predictably.

On the other hand, most of us—myself most certainly included—are not Top Guns, and when we start to think of ourselves as being capable of “flying the crate it came in,” we’re setting ourselves up to be bitten by any airplane we fly, be it a Glasair, a GlaStar or a Cessna 150.

The Glasair demands a certain amount of respect from its pilots, and I found IFR training in the airplane to be an excellent way to build the proficiency necessary to confer that respect with confidence.

Of course, the good pilot never stops learning. For my part, I have a tremendous amount yet to learn about flying instruments and flying the Glasair. Getting this rating has just fired me up all the more to keep doing both.

Now, Bob, about getting my ATP in the III.