Deburring rivet holes: A 3″ Scotchbrite wheel in a variable speed drill motor does a very fast job of deburring long lines of rivet holes in skins. Of course you should etch, Alodyne, and corrosion proof the 1″ wide strips where you’ve damaged the Alclad surface.

Deburring rivet holes: A 3″ Scotchbrite wheel in a variable speed drill motor does a very fast job of deburring long lines of rivet holes in skins. Of course you should etch, Alodyne, and corrosion proof the 1″ wide strips where you’ve damaged the Alclad surface.

–Al Sibley

Stupid metal workers tricks: Learning metal work isn’t just learning how to do it right, we all sometimes make mistakes and we need to know how to correct them or at least cover them up cosmetically! (Amazing how good it all looks when finish painted!). Theres a wealth of information about metal working on the net, from some obviously very knowledgeable metalworkers, so with some considerable trepidation I take computer in hand to present this:

The most common problem is “figure-eighting” the rivet hole when drilling out a bad rivet: Other than a supply of the famous “Figure-Eight” rivets, usually a larger size rivet has to be used, but “Some People” have been known to put a dab of Bondo in the screwed up hole along with the rivet, thereby creating the illusion of a undamaged skin where the rivet now resides. Carefullly wiping the area clean will help complete the subterfuge! (If the underside of the hole is too enlarged for the rivet to hold, rivet in a piece of metal as a back up).

Did you know that metric sized rivets are available? Guess what, they are a little oversized from US standard AN sizes… Hmmm, food for thought? The heads, though bigger, are virtually indistinguishable from their neighbors.

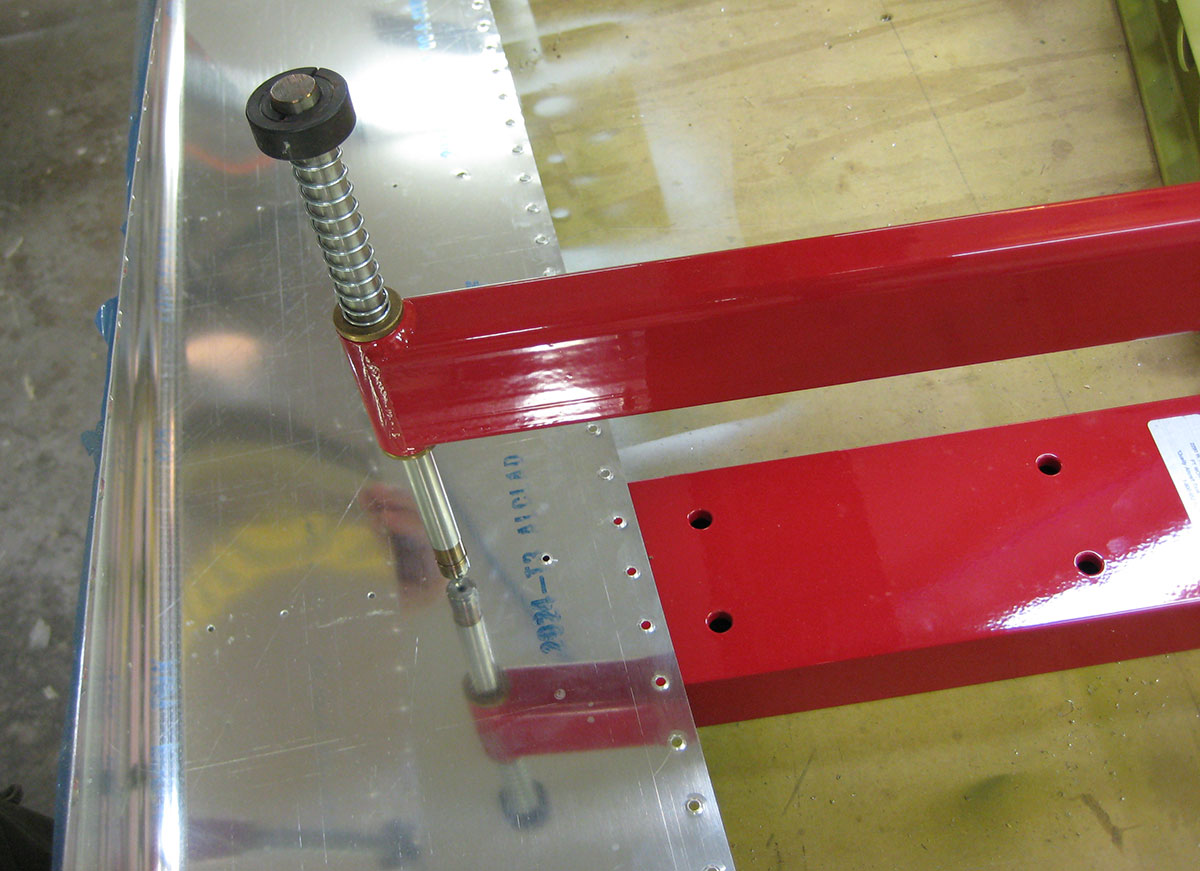

Metal needs to be pulled together when fastening with rivets. Clecos, finger clamps and c-clamps do a good job, (I even use bags of sand, rubber straps and twisted twine), but sometimes the surfaces just won’t hold tightly enough for riveting, there’s that little space between them. This procedure requires that you obtain some yellow plastic body putty squeegees. These are tapered. Cut one into strips about a half inch wide and drill rivet sized holes in each end. When the metal skins need to be pulled tight while riveting, put one of your little strips over the tail end of the rivet, using a thickness that makes it just flush with the end. Lightly buck the rivet, the idea being to “bulb” the tail, thereby creating a swollen end of the rivet that on the next try, when it is finish bucked, will pull the metal pieces together tightly. (This works when a longer rivet must be used to “fill” in an oversized hole, too). Both work very well and don’t require much practice! Other than plastic, thin sheets of lead work well, too, but I don’t like to handle it.

Back riveting: This is my favorite method because mirror-finished skins will not be marked while doing this and I believe work hardening the buck tail provides a stronger rivet!). It requires a special tool for banging the tail down.

–Bill Nash

General sheetmetal tips: A few tips that have been provided to me by others, or that have dawned on me in one of my more productive moments:

- Place masking tape over the tips and/or edges of the any riveting tools. Whether you are using a squeezer or a riveter, the head of the rivet being squeezed or driven and the surrounding skin, flanges or spars will be protected from scratches, dings and dents. Smileys should be added to computer messages – not skins. 😉

- Round and smooth all edges and corners of bucking bars with a deburring wheel or with a file and sandpaper. It will help keep down scratches in your sheetmetal. Use masking tape to tape all edges of bucking bars. Also keep the bucking face of the bar polished.

- Fabricate special bucking bars from your existing bars or from raw steel which can be purchased from your local steel supplier. I bought a load of steel scrap from a local steel shop for $2.00. They let me walk through their shop and pick up what I wanted off the floor. They eyed what I got and said $2.00! With that raw stock, and the commercial bucking bars that I already had, I have been able to fabricate a bucking bar for whatever I have needed. If I am working in a tight area or in some hard-to-reach area, 1) I decide what I need, 2) pick up the closest bar to what I need, and 3) grind and polish it into what I need. I find that I can do so with my bench grinder which has a grinding wheel on one side and a 3M deburring wheel on the other.

- You may need more half-sized rivets than S-H provides. Yet your rivet cutter probably only cuts to whole sizes. An easy fix is to select the next larger rivet, set the cutter at next shorter rivet size, and then slip a thin piece of aluminum (a shim) under the head of the rivet. When the cut is made, the rivet will be “about right.” I took a piece of a rib flange, drilled .40 and .30 holes in it, and use it as a spacer when cutting half-size rivets. The flange came from scrap that is cut from two ribs during the horizontal stabilizer construction. Unfortunately, most rivet cutters do not cut shorter than -4, so this method won’t work to make a -3.5 rivet using a rivet cutter. But you can use a wire cutter-stripper instead (not dikes, but the combination wire cutter and stripper). Simply fashion your aluminum shim for your wire cutter instead of your rivet cutter.

- When bucking rivets inside an assembly such as the rudder or horizonal stab, hang a small flourescent drop light inside to illuminate the inside of the assembly. That way, you can see what you’re doing and the light will not produce heat.

- When removing excess aluminum, tools that prove handy include handheld belt-type sanders, palm-sized orbital sanders, and deburring wheels. Naturally, a bench-type belt sander and a drill press with cylindrical sanding disks work wonders, but for removing excess metal from large assemblies such as a horizonal stabilizer, these tools simply don’t work as well. The belt-type sander will remove excess sheet quickly – and therein lies a potential for harm! Don’t use the belt sander to remove small amounts of sheet. Use the palm-sized orbital sander for this purpose. A medium-grit sanding sheet is fine (80 or 100 grit). If you mark the inside of the overlap with a red felt tip pen flush so as to create a red border area, then sand to the outside edge of the red area, you will not cut into the skin too far. You then can remove the remaining stock by using the palm-sized orbital sander, a file, a sanding block, a deburring wheel, or some combination of those tools.

The small (3″, I believe) 3M deburring wheels which can be used on drill presses, pneumatic or electric drills, or pneumatic die grinders will work wonders at deburring, shaping and edging. Some aviation supply houses sell these jewels for $3-$6 each! They also ask about $5 for the mandrel. Suppliers at Sun ‘n Fun were selling *two* wheels and a mandrel in a plastic pouch for $2!

–Joe Colquitt

Edge bending: My memory was jogged, while bending the wing skins on the Glastar project, of a hint that may make the job go a little easier for you. Most of you have probably noticed that, when using the Avery edge bending tool, that the tool tends to get scratched up and that the tool will roughen up your smoothed edges on the skin. When I was doing the RV-6 skins, I’d take the wheels off and polish the surface, but the smooth surface didn’t last long. To make things go really smooth, I stuck on some self-adhesive UHMW (.010″ thickness. The same stuff I used on my flaps at the wear point.) With the UHMW on the tool, edged bending is effortless and the edges of the skin are no longer roughed up.

–Bob Skinner

Edge bending: The operative word here thought is “slight.” It should be barely perceptible to the human eye and that’s “slight.” Most people err to overdoing it. I was RV-experienced and had the tool so “why not.” It worked fine. Be careful thought. It’s easy to overdo. You don’t really “bend” as much as you just slightly “encourage.” Again, DON’T OVERDO IT! I’ve seen too many people put 10 degree bends in skins thinking that’s what was called for.

–Joe Colquitt

Edge bending: The Vosberg forming tool adds a nice touch to overlapped skins. I even used it on the wing nose skins. It is tricky to use, however. Draw it toward you slowly and keep pressure on the inside edge or it will slip to the outside and you will have a nice diagonal crease. Also, note that the instructions call for a slight crease, almost imperceptible. Do not crank the vise grip down a lot and do it just once. It is definitely worth the effort and slight expense.

–Monty Rogers

Squeezers: As most of us learn, the usual hand squeezers require unusual effort for 1/8″ rivets. I can mange 10-15 minutes of squeezing, but my wrist and forearms tire to the point where I can’t fully form the shop head. For a while I used a gun for the final compression, but then recalled a technique from the auto repair world called a breaker bar. The application here is two 10″ lengths of 3/4″ id pipe slipped over the hand squeezer handles. I lightly taped the handles first to prevent scratching and then taped the front edge of the pipe to its handle. The resulting 5″ handle extensions provide enough mechanical advantage for another 10-15 minutes of squeezing. If the rivet line is still not finished I call my wife. I insert the rivets and control the squeezer by gripping the handles about 4″ from the end. She places her hands on the remainder of the extensions and pushes on my command. The two of us are able to squeeze 1/8″ rivets.

–Bruce #5368

Pulling together metal with rivets: Many amateur builder have never used solid rivets before. Most fasteners such as bolts and screws and even nails, force parts together as they fasten. .Even pop rivets draw parts together. Solid rivets do not. SH does not address drawing metal parts together with rivets. Just driving a rivet does not squeeze the metal parts together, unless they are already touching. In fact, if a gap is allowed to remain between parts being riveted together, setting the rivet will guarantee that the gap will be there for ever.

I noted an earlier tip that addressed this problem with some plastic material with a drilled hole placed around bucked end. I would guess the plastic is wapping the metal together at the same time the rivet tail is expanding. Would work if the plastic was the right thickness and softness. However if you are into driving rivets all day long, this would be too time consuming.

Factory riveters refer to pulling the metal together with a rivet as “drawing”. If a team is riveting and the metal parts have a small gap, the bar man will say “swell”. The gun man will tap the rivet lightly. Next the bar man will place the point of the bucking bar next to the rivet shank and say “draw”. The gun man will tap lightly. If the rivet was swelled enough (not over swelled), the parts will slide together and stay that way. If the river was (under swelled), the swelling and drawing process must be repeated. Once the parts are drawn together, you finish riveting in a normal manner.

When using this method to draw thin metal parts together, using the bar point will not support the thin metal, full circle. Instead of sliding the part down the rivet shank, it may just bend the metal under the bucking bar point. Thin metal requires a bar with an appropriate sized hole that surrounds the rivet shank and fully supports the thin metal. This same special bar is also a must for supporting the metal around a bucked head when a bad rivet is being punched out.

–Orville Eliason & (Son) Kit #5298

Removing scratches: For light nicks, dings and scratches, it is best to copy the same finish as the existing material if possible. I use 220 grit emery strip cloth and pinch the cloth over the defect with my thumb, then draw the cloth to wipe out the mark. I check my work with a 10X magnifier. This leaves a finish the is virtually the same as SH puts on their part interiors. Some parts such as ribs have been jitterbug sanded and it may be impossible to match the pattern.

Remember that material reduction less that permitted by the specification stock thickness (usually nominal +/-5%) in a high stress area can be bad news. It may be wise to check the stock thickness in the area reworked and replace it if in doubt.

Alclad surfaces are a whole different story of which I have no answers. I know if you try to polish the Alclad, the clad will be worn through and there will be two colored surfaces showing, bright pure aluminum and grey 2024.

–Gus Gustavson