Several years ago, Tom Needham – missionary pilot in Cameroon – experienced an unforeseen downdraft on final approach into one of the many villages he serves with his Sportsman. The terrain is mountainous and the airstrips are mostly one-way, with steep uphill approaches. Tom recalls that it was a very short strip and he was afraid that if he applied full power the fully loaded Sportsman would have overshot the end of the strip. So he applied partial power but it wasn’t enough and he stalled it in. In retrospect, Tom told me, “I should have given it full power, and worried about how to get stopped after getting the stall recovery taken care of, although, on second thought, that could have caused more damage and injuries. As you know, these things happen so fast it’s hard to remember all the details.”

The result was the plane impacted the ground with too much vertical energy damaging the landing gear and cage structure in the immediate area of the taildragger gear truss tubes.

That incident resulted in my first trip to Cameroon to assist Tom in repairing the cage. Unfortunately, all we had at our disposal was an oxy-acetylene welding outfit and we had great difficulty getting enough heat into some of the critical tube clusters to get adequate weld penetration. As a result, Tom has been able to keep the plane operational, but only after performing periodic inspections and follow-up weld repairs. In some of the recurring problem areas, he cut permanent access holes in the fuselage shell with inspection covers in order to repeatedly inspect and weld. As the Sportsman cage issues grew worse over time (and the fuselage exterior increasingly lost cosmetic luster) Tom called Glasair Aviation and asked if it would be possible to separate the fuselage and replace the cage with a new one.

Tom’s original cage was based on a 2350 lb gross weight. Since then, the company has developed the carbon fiber option (2500 lb GW) with bigger lift struts, plus wing and cage structural beef-ups. Tom elected to purchase the 2500 lb cage and even specified a few more minor modifications to suit the rigors of rugged mountain bush flying.

Langair Machining has developed a set of 4” taller, 8” wider landing gear that have been installed on both GlaStar and Sportsman taildragger aircraft. I agreed to travel back to Africa and work along with Tom and Terry Rushing who is a long-time friend of Tom’s and director of Wings as Eagles in Oshkosh, WI. Terry has commercial, IFR, and A&P ratings and frequently travels to Cameroon to assist Tom with repairs, condition inspections and flying duties when extra help is needed. We also had help from Sam Sanderlin (owner of Tom’s previous GlaStar) and Anders Swanson who was serving as a missionary apprentice who turned out to be a quick learner and great help with airplane surgery! We also received periodic help on the project from some of Tom’s local young Bamenda men.

The order was placed for the cage and soon it was air-freighted to Cameroon to be on site prior to our arrival. We estimated that we could accomplish the cage swap in approximately two-weeks. (a common theme around here!)

Terry arrived 4 days ahead of me in order to completely disassemble the plane. This included removing EVERYTHING but the rudder. This meant the engine, windshield, instrument panel, doors, wings, stabilizer and elevator were all removed and stored. The fuselage was internally stripped of seats, pans, wiring, fuel lines, cables and pulleys, rudder pedal assemblies and well…everything!

Tom flew into Yaounde to pick me up in the GlaStar he built and operated prior to the Sportsman. The following morning we flew approximately 1.5 hours from Yaounde to his home field in Sabga in ‘pea-soup’ thick smoke and haze. The local farmers and cattle ranchers all burn their fields and pastures to rid them of unwanted vegetation and weeds in the dry season creating near IFR conditions. Arriving home, Tom was greeted by his wife, Barb and learned there was a pregnant woman experiencing difficulties in one of the villages he serves with an airstrip. After a brief re-fuel, Tom was back in the air to pick up the patient and deliver her to a local hospital to receive medical care. Nothing unusual about that for Tom, as this is a big part of his work; to help with the needs of the villages served by the Sportsman.

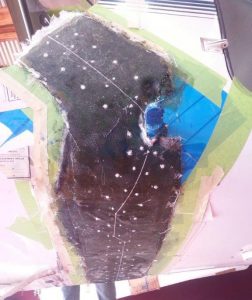

On arrival, I changed clothes and got right to work with the team. The first task was to lay-up some exterior molds for use as re-assembly fixtures for the shell. This involved marking out cut lines, then covering the surrounding areas (8 inches wide) with mylar tape to protect the fuselage. After a thin coat of wax was applied to the mylar, we saturated multiple layers of 2 oz. mat cloth in order to build up a sturdy “mold” of approximately 1/4” thickness. The molds cured overnight and the following day we drilled #40 holes through the molds and into the outer skin of the fuselage. The purpose of the holes was to be able to perfectly match the fuselage halves back together with a combination of (longer) draw clecos and standard ones.

Once the cleco holes were drilled, we removed the molds and started cutting the fuselage apart into a forward and aft portion. Not long after, the worn out cage was free and we had two pieces of a composite fuselage and a new cage we hoped we’d someday get back together. During our discussions in the planning phase of the project, I reassured Tom and Terry that this job was going to be a “piece of cake.” To be perfectly honest: there are sometimes projects I take on (like sawing an airplane in half and gluing it back together) where I stand back and say to myself, “Setzer, you’ve really gotten in deep this time!” Well, this was one of those times for sure, and I think the three of us were secretly feeling the same anxiety, but we just dove into the task list as the TWO-WEEK CLOCK was silently ticking away…

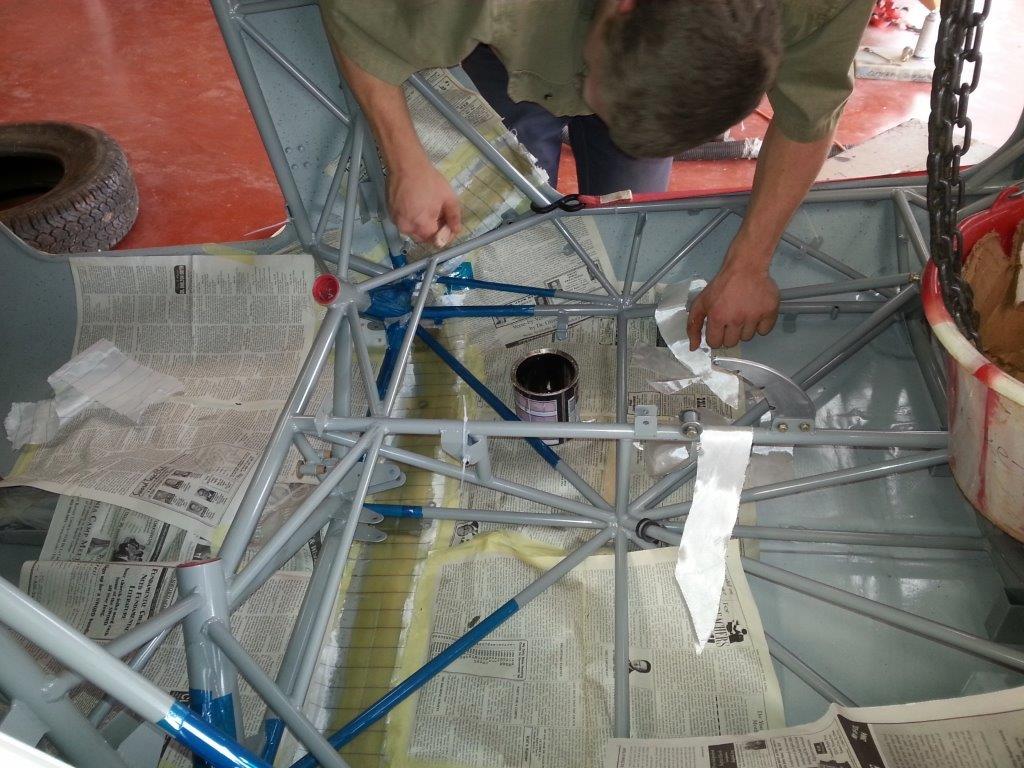

First, we had a lot of sanding and preparation to do. We wanted the interior to look like new, so we sanded the insides using a pneumatic orbital sander with compressed air. Tom uses an automotive generator run by a Pelton wheel driven with 40 psi water pressure delivered via piping from a water source on the ridge above his home. The generator charges two, large 200 amp DC batteries with an inverter to create AC current. This power is used for light fixtures and some home appliances. For larger power demands like an air compressor or welder, he simply fires up a generator. While sanding the interior, we discovered past fiberglass repairs that needed some cosmetic attention even though the fuselage in this area isn’t structurally load bearing. It was infinitely easier this time since there wasn’t a cage in the way to rub knuckles on. Once the sanding and fiberglass reinforcing was accomplished we smoothed all the rough edges out with a little body filler, taped off the cut-edges to be re-joined and sprayed the forward and aft interior surfaces with gray primer and Zolatone.

Prior to separating the fuselage, we marked a few reference measurements between the cage and exterior fiberglass surface to verify if the new cage was to be positioned the same as the old one. Even though we had a good method to re-join the composite shells, the cage would be floating inside the shell a bit until it was secured. The front of the cage would fit back to the firewall through the engine mount holes, so we didn’t have any concern about cage position in front, so we carefully referenced the position of the lift strut attach lug at the back of the cage vertically up and down and side-to side (centering).

The rudder pedal assemblies and master cylinders were installed on the cage before we placed it inside the fuselage making the job much easier. Tom installed the axles, wheels, brakes and tires on the new main landing gear struts. To reduce efforts in Africa, the main gear had been positioned and drilled on the cage back at the Glasair factory in addition to laminating fiberglass fairings and steps.

I recall it was at least 5-6 days before we inserted the new cage and joined the fuselage shells back together. The fiberglass molds worked like a charm in joining the fuselage perfectly back together. With a little pushing, pulling and shimming of the cage, we were able to get the fuselage back to it’s exact position vertically and within a 1/16” tolerance side-to side. It turned out that the aluminum brackets securing the cage to the fiberglass shell on the aft, lower tube didn’t quite line up with the new cage tabs, so we quickly fabricated some new ones and in one case we taper sanded and filled in the existing fuselage holes with fiberglass plies and sanded the exterior flush. This allowed us to re-use one pair of the brackets and drill new holes through the fuselage. Once we had 30% of the cage tabs secured to the fiberglass shell we then laminated two plies 7781 cloth overlapping the interior seams across the cut lines.

The following day, we removed the clecos and molds and began taper sanding the external fuselage skin plies. A 50:1 taper ratio meant we needed to scarf sand the plies 1.5” on either side of the cut line, for a 3” wide seam. We laminated two exterior plies of 7781 cloth to these seams. Before the exterior seams were completely cured, we installed the main gear. This was a big milestone and enthusiasm booster as the plane once again was standing on its own two feet. Sensing an opportunity to get away from the sticky, smelly fiberglass work, Terry dove headlong into the job of installing the engine and all firewall forward components. If Terry, Anders and Tom hadn’t done such a meticulous job of labeling, bagging and organizing all the pieces, brackets and hardware, the project could have easily slid into a third week. It always takes much longer to re-assemble than disassemble, but the time spent organizing and labeling parts for re-assembly really paid off. Our momentum and enthusiasm picked up day by day as more of the plane came steadily back together. We had planned to install a rear facing seat similar to Glasair Aviation’s aft seat installation, but made the decision to set it aside until we were assured of success with completion and test flying the restored aircraft. Also, Tom shared some ideas of how he might want to modify it to allow for ease of removal or folding as he occasionally needs to place hospital-bound passengers on a stretcher inside the plane.

I recall it was around Tuesday of the 2nd week when the wings, stabilizer and elevator were re-attached and rigged. That night I went to bed early and awoke at around 10 pm with intense abdominal pain. “Not here, not now!”…were my thoughts as I paced back and forth in my room above the hangar. I have previously experienced a few kidney stones and once you’ve had them, there is no doubt when they return. I didn’t want to bother the others as we were all needing rest, but finally gave in and told my team-mates I was in trouble and needed to find some pain medication. Tom, Terry and Sam drove me to the nearest clinic over the roughest road I’ve ever been on, but to my great relief, they had some medication to knock down the pain. I spent the remainder of the night there but was out of commission in helping with the remaining reassembly work. Sam drove me to a hospital in Bamenda the following day and after a long wait I received a CT scan. Tom test flew the Sportsman that afternoon coming straight to Bamenda and med-evacing me to a hospital to see a visiting volunteer American urologist. I wasn’t sure which was going to kill me first; the test flight of a plane that was recently chopped in half or the kidney stone, but really didn’t care which it was as I just wanted some relief. I suppose it was ironic (and a huge blessing) that I was the first medical mercy-flight recipient of the newly refurbished Sportsman. I was in pure agony while Tom was in pure joy remarking that he was really liking the feel of the sturdy cage and taller gear. I was happy for him, but honestly I was much more interested in getting some pain pills.

(Note from Tom: the visibility was barely a mile in haze that day and the hospital airstrip is surrounded by close-in mountains rising 4,000′ above the strip. I told Ted to look for the mountains while I looked for the airstrip. It’s a good think I didn’t know just how bad Ted was hurting. Ted is a man’s man for sure. He’s one tough guy and such a tremendous friend and helper of this ministry.)

The CT scan revealed no stones, so the Urologist surmised that I probably passed it. I wasn’t convinced and asked for a pain prescription to get through the long (22 hr) commercial flights home, lasting two days with layovers.

The next morning, after my emergency test flight to the hospital with Tom, we loaded the Sportsman and exchanged good-byes with Anders, Sam and Tom’s wife Barb and daughters Kathy, Elizabeth and Bethany. I elected to curl up in the back with the bags as I was desperate for some sleep. Besides, the visibility was very poor and who would argue against two experienced IFR rated pilots (Tom and Terry) up front. After the successful 1.5 hour flight back to Yaounde, still lying in the back, I wondered why Tom added power just before touch-down and momentarily got airborne again. The landing seemed ok, so I surmised he just wanted to fly the length of the runway to avoid a long ground taxi.

Exiting the Sportsman, I learned that they had to pop back into the air to avoid hitting a woman who was crossing the runway and not bothering to look for aircraft. In fact, this wasn’t an unusual experience according to Tom who pointed out that there are well traveled trails across the runway in several spots. No big deal. After all… this is Africa!

Terry and I sat together from Yaounde to Brussels where we parted ways after a 5 hour layover. My United Airlines flights would take me through Chicago to Seattle. Terry’s flights were to Oshkosh through Washington DC. On my flight to Seattle, I was seated next to a man who I couldn’t help from overhearing his conversation with a woman next to him. It sounded like they were doctors, so I couldn’t help but interrupt them and ask for a little free medical diagnostic advice since my CT scans in Africa showed no signs of a stone but there was no doubt that something was still very painful in my abdomen. I mentioned to them that “while I was repairing an aircraft in Africa, I experienced what I thought was a kidney stone attack, etc.” The man was indeed a doctor and said he was more of a “mechanic” than a diagnostic doctor since he was a gastrointestinal surgeon. He advised me to ask the Seattle doctors to also check to see if perhaps I might have gall stones. After politely answering all my questions, he asked, “What kind of plane were you repairing in Africa?” when I said it was a Sportsman he questioned further: “A Glasair Sportsman?” I replied, “Yes!! Do you know about the plane?” He enthusiastically replied, “My name is Dave Gauger and I’m a Glasair builder from Tacoma, Washington”.

What a small world indeed.

Tom has been in communication with Terry and I since we returned home and we are pleased to report the plane is performing better than Tom anticipated. He loves the new landing gear and renewed confidence in the heavy duty steel cage. Mission accomplished.

I want to personally thank Tom Needham for the difference he is making in the lives of those who live in his area of Cameroon. His family has been there for 25 years and have earned deep respect from many Cameroon residents. I find it very satisfying to know that the Sportsman (and Sam Sanderlin’s GlaStar) is used on almost a daily basis to reach out to those who live in remote villages to help with their needs. I’ve had prior first-hand experience flying with Tom to deliver needy patients to the hospital where the alternative may have been certain death. Tom occasionally sends me emails with heart-warming stories of the medical emergencies he rushes to serve with the Sportsman and the lives he touches with his family’s ministry.

I have the same thankfulness and appreciation for Sam Sanderlin and his family who purchased Tom’s GlaStar and serve very similar missionary goals in the same area of Cameroon. We had time to assist Sam in making some cosmetic gear fairing repairs and replace the windshield on his Glastar. A few years in the future, this aircraft will be due for a few upgrades and a general cosmetic overhaul.

I also want to give a huge THANKS to Terry Rushing. He was critical to the success of the Sportsman cage project. When Tom and I initially discussed the possibility of tackling the project, we (old guys) decided that we needed someone who could infuse some A&P experience and extra energy into the mix. Terry was the natural choice since he had previously helped with fabrication and assembly of Tom’s Sportsman in Oshkosh, WI. We were both very grateful to have him as a vital part of the team. In fact, he was the true team leader as I arrived late and was forced to leave the project at a critical stage. My contribution centered around the plan for fuselage separation and re-attachment, but the steady labor force was provided by Terry, Tom, Anders, Sam, Franklin, Ernest, and Edwin.

The caloric energy that kept us moving at a fast pace was provided by Tom’s loving wife Barb and their daughters Kathy, Bethany and Elizabeth who worked tirelessly in the family kitchen to feed our hungry crew (plus other daily visitors) three big wonderful meals a day, plus many servings of hangar drinks and snacks in-between. Thanks ladies for taking such good care of us and providing a true home-away-from-home!

Postscript:

The kidney stone pain plagued me all the way back to Seattle but I managed to keep it reasonable with the pain medication. Arriving home, my adult children drove me to Swedish Hospital ER where a resident urologist located the lodged kidney stone with an old fashioned X-ray and removed it with an internal laser procedure.

My trip to the Swedish ER lasted a little longer than I anticipated. In addition to a simple kidney stone stuck for 6 days, I was diagnosed with an obstructed bowel, blood clots in my legs and lungs, and when the urologist went after the kidney stone, he discovered bladder cancer. However, the good news is the cancer was in the early stages and he removed it then and there. How many people are as fortunate as me to be told after surgery they have some cancer… but it is already gone! The blood clots are dissipating and I’m feeling about as back to “normal” as one can get only one month later.

My buddy, Alan Negrin advised me to re-join AOPA and sign up for their medical/legal services. I did. AOPA has offered me some very sound advice for how and when to reapply for my third class medical and their medical advisors feel I have a very good chance of receiving it as long as I follow their advice. If I encounter problems, they will go to bat for me. This service they offer costs $99 above the $49 basic membership fee—worth every penny.